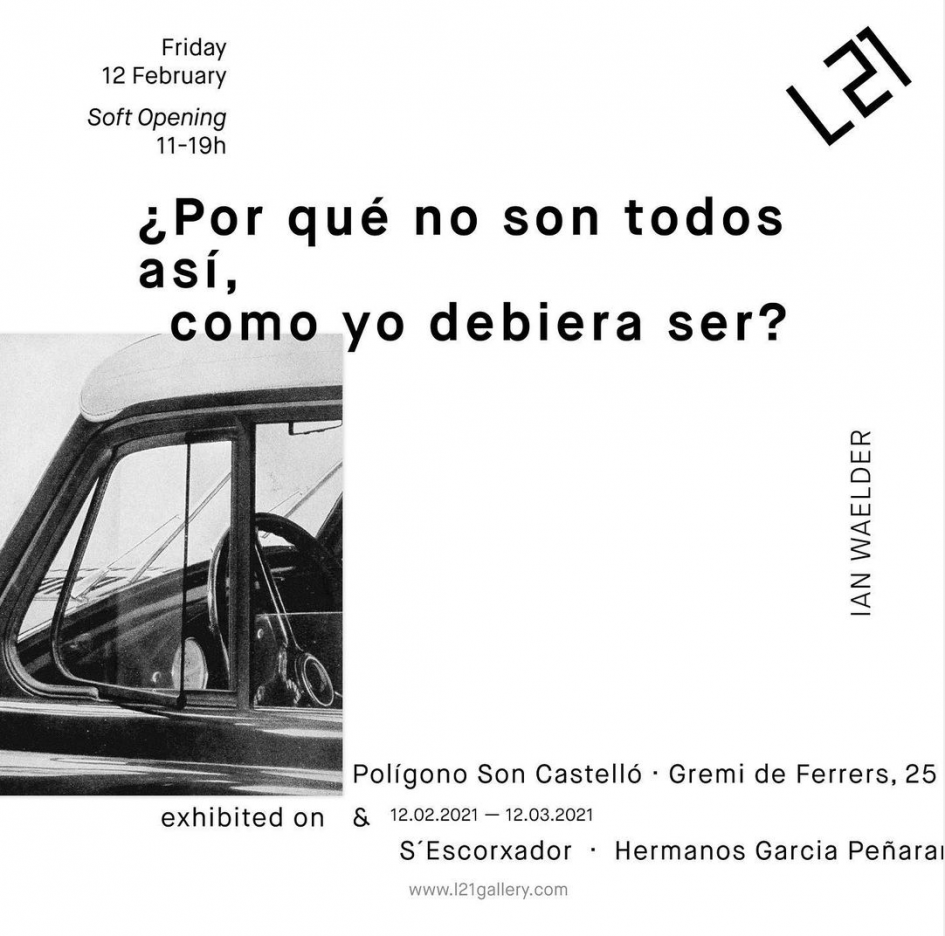

12.02. – 12.03.2021

L21 Gallery, Mallorca

Venues: Gremi de Ferrers, 25 & Hermanos García Peñaranda, 1A.

www.l21gallery.com

The opening sequence of Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938) is recognised for its exacerbation of neo-classical beauty, strength and racial purity. Its closing scenes, however, depict a different embodied reality: athletes struggle with the vulnerability and exhaustion experienced at the finishing line, the unavoidable halting of speed wrought by their overextension, and the need to be held, covered and cared for.

Defeat and despair are the visible traces with which Riefenstahl ends one of greatest political propa- ganda masterpieces of the twentieth century. The ending scenes of her filmic ode to the extravagant site of Third Reich political theatre that was the Berlin Olympics of 1936 is the departure point of Ian Waelder (b. 1993, Madrid) to explore the continuum of mourning and reconstruction of racialised and dehumanised lives.

Despite winning several gold metals that year, the film overlooks the presence of 18 African-American athletes representing the United States during a particularly violent period of the Jim Crow racial seg- regation laws wherefrom German jurists based and codified the Reich’s race-based legal philosophy.1 This same legal framework disqualified Jews as Reich citizens with political rights and enabled the destitution of millions of Jewish folk living in Germany, among them, Friedrich Wälder, the artist’s grandfather.

Between the years from 1935 to 1940, Wälder like millions of Germans acquired a compact car pro- duced by the German car manufacturer Opel. Named Olympia in anticipation of the Berlin Olympics it was Germany's first mass-produced car. By 1939, however, Jews were now no longer allowed to own cars and Wälder was forced to trade his at a fraction of its value. Having been detained at the Welzheim concentration camp for four months between 1938 and 1939, Wälder used the currency to escape Stuttgart and flee to Chile, with the aid from a Chilean friend with whom he studied at the Technische Hochschule in Stuttgart and from an uncle in Strasbourg.

During transit, Wälder, a pianist, lost his music library as well as all his compositions. Arrived in Santi- ago he signed for the music label Odeón under the name of Federico Waelder Sander and in the mid- fifties he relocated to Antofagasta, where he signed as an exclusive musician of the Antofagasta Ho- tel. Passionate about photography, he was the only family member to have survived the genocidal Nazi regime. It is from a note his grandfather wrote to his father, the sculptor, Juan Waelder, that the artist borrows the title for this exhibition, “They say that as a pianist, I am a good photographer and vice versa. And don’t forget: why aren't they all like that, like I should be?” A prescient metaphor for his political life.

At L21 in Son Castelló, the only existing record of Federico Waelder’s jazz improvisations has been mixed with another sound work All My Shoes (Spooky drums n1) (2018) immersing the visitors in an auditory environment of remembrance. Looped in the galleries, the sound piece was discovered by the artist during the first lockdown and played monthly on a German radio station. Now published by Heutigen Records as limited vinyl edition accompanied by a small publication, the sound piece en- velops a new series of large-scale canvases stretched with inkjet stills from Riefenstahl’s Olympia. Exposed on raw linen, images depicting the athletes’ exhaustion overturn the celebratory theatricality of national organised sports. They are overlayed with technical descriptions of the Opel Olympia, as well as advertising quotes written in German language using oil over the unprepared linen. Removed from their original context, these sentences resonate in the refrain of concrete poetry and political commentary.

The closeup of his grandfather’s hands covering the LP sleeve, inspired Waelder to use sculpture’s haptic register – the sense of touch – to broaden his genealogical research. Waelder invited his father to reproduce his grandfather’s Olympia. Together, father and son created an awkwardly sized, plaster reproduction of the car carefully displayed atop of a plinth. In its carvings resonates the care and fragility with which the artist recounts his grandfather’s survival. Waelder attempted to locate his grandfather’s car on eBay and in the depths of car afficionado forums in a strange play on prove-

1 The Nuremberg Laws are a set of anti-Jewish statutes enacted by Germany in 1935, consisting of the Reich Citizenship Law, the Law on the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, and Law for the Protection of Hereditary Health.

nance research. From one of these online forums, the artist assembled 145 frames from different films, documentaries and tv series where the Opel Olympia figured as background vehicle, was used in a short scene or was used by a character in a chase scene. A selection of these stills is printed on a new series of risographs on L21’s gallery at Calle Hermanos García Peñaranda and is juxtaposed with Waelder’s handwritten annotations containing the film title, follow by type of media, year, catego- ry of the car, and where available country of origin. In the trajectory between galleries, and his explo- ration of the Opel Olympia’s afterlives demonstrates how the complexity of our political and personal narratives continues to permeate our visual and material cultures in trajectories that might go other- wise unnoticed.

Based in Frankfurt, Waelder is the first in his family to return to Germany after his grandfather’s forced departure. In a gesture reminiscent of Latin American Conceptual artists from the 1960-70s, Why aren't they all like that, like I should be? is a personal yet deeply political statement that stages art's role in responding to history in conjunction with poetry and painting and across multiple sensory regis- ters.

— Sofia Lemos