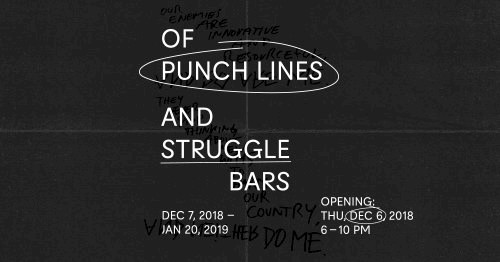

Anna McCarthy

Casey Jane Ellison

Dora García

Il-Jin Atem Choi

Lennart Constant

Michael Pybus

Michael Riedel

Su Xia

December 7, 2018 – January 20, 2019

TOR Art Space

Allerheiligenstrasse 2–4

60311 Frankfurt/Main

Opening: Thursday, December 6, 2018, 6–10 pm,

with a musical performance by Anna McCarthy & Manu Rzytki

a.k.a. WHAT ARE PEOPLE FOR?, 9.00 pm

Curated by Il-Jin Atem Choi and Celena Ohmer

Artistic Coordination: Janusch Ertler

In cooperation with Städelschule.

From an anthropological point of view, comedy is a consciously or subconsciously experienced part of everyday life, which is geared towards being able to coexist in a civilized way. In addition to its functioning as some kind of valve, it offers the possibility of breaking up rigid patterns of order and hierarchical value systems. Comedy has long since penetrated beyond everyday life into areas such as politics and journalism, and aims to challenge supposedly final axioms by negating traditional stereotypes, inherited role clichés, and societal norms and obligations.

Contemporary art often inhabits a weird, absurd, cynical, and radical level. Historic movements of avant-garde modernism such as Dada or Surrealism established the humorous moment as a subversive strategy to push for the very shift in perspective that comedy nowadays also establishes.

The most obvious difference between comedy and art is the dominance of the "joke"-structure in comedy and the associated function of being able to make someone laugh. The so-called "punchline" forms the core of the joke as the moment of denouement to which everything else boils down to (the "premise" and the "set-up"). According to the Slovenian philosopher Alenka Zupančič, the punchline embodies a kind of short-circuit between two sides that are essentially not accessible to one another and thus leads to the paradox of a possible impossibility.

Comedy has often been and still is being conceptualized as inherently critical towards ideology: The king falls flat on his face, because he slipped on a banana peel, everyone laughs and thinks he is but a common man. Yet, it is precisely at such a moment that an ideology of being in power and also maintaining it takes its fiercest effect, for the laughter of the ruler over himself perpetuates his hierarchically structured power. Contrary to this "conservative" conception of comedy, Zupančič suggests the figure of thought of the impossibility of travelling from one side to another without ever having to cross a border, which corresponds exactly to the image of a Möbius strip. This kind of paradox, to be able to think about possible impossibilities, can in the best possible cases of comedy and art be made palpable and visualized. Especially since German Romanticism, there has been a tendency to make use of some form of “two-valued logic”, which operates with varying degrees of truth contents of statements leading to certain dichotomies (such as true/false or form/content). This almost dogmatic thinking in dichotomies may be bypassed by means of paradoxes as figures of thought such as the one mentioned above.

Not particularly known for comedy, Niklas Luhmann explored (among others in The Art of Society) complex formal questions by means of the so-called “medium-form distinction”. Marching on, he indicates that the concept of form can be described as “the operation of distinction as an instrument of observation” and eventually ends up at a fundamental paradox of form: The form within the form is the form of the enclosing form. This statement is, in a manner of speaking, the metaphorical concretion of comedy and art. Both are, in the best possible cases, non-logical entities that can still transmit some kind of truth.

Based on these considerations, the exhibition project OF PUNCH LINES AND STRUGGLES BARS will investigate to what extent art and comedy can, in the most direct case, operate congruently as art. In doing so, the focus may best be on the specific form of a specific artwork, because as described above, chances are that on this self-referential level (not the two-valued logic but what Luhmann calls “Zwei-Seiten-Form”, i.e., the form of two sides) one can most clearly articulate what constitutes the common parameters of comedy and art.