Nathalie Grenzhaeuser | Magdalena Jetelová | Clare Langan

03.06.-11.09.2022

Artists and cultural workers are like seismographs of constantly changing social processes and structures. Today it is especially the climatic changes on a global scale that are becoming increasingly visible not only in nature and landscape, but also on the social plane. Humanity, if it wants to survive, is faced with new and unprecedented challenges.

In her works, the Berlin artist Nathalie Grenzhaeuser examines the relationship between architecture and topography, often against the background of settlement histories in remote parts of the world. With the gaze of the photographer, who travels to inhospitable regions without regard for herself, she searches for visible traces of developments and changes in ecologically fragile landscapes, such as the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, for whose rich resources many nations have wrestled since its discovery. In her often large-format photographs, Grenzhaeuser shows the striking, wild beauty of the barren landscape, which brings her into a dialogue with aspects of human usage and the latest environmental research. This exciting contrast and the inhospitable landscape sometimes cause discomfort in the viewer. At the same time, the photographer succeeds in evoking associations with 19th century Romantic paintings and the science fiction genre in literature and film using her specific visual language.

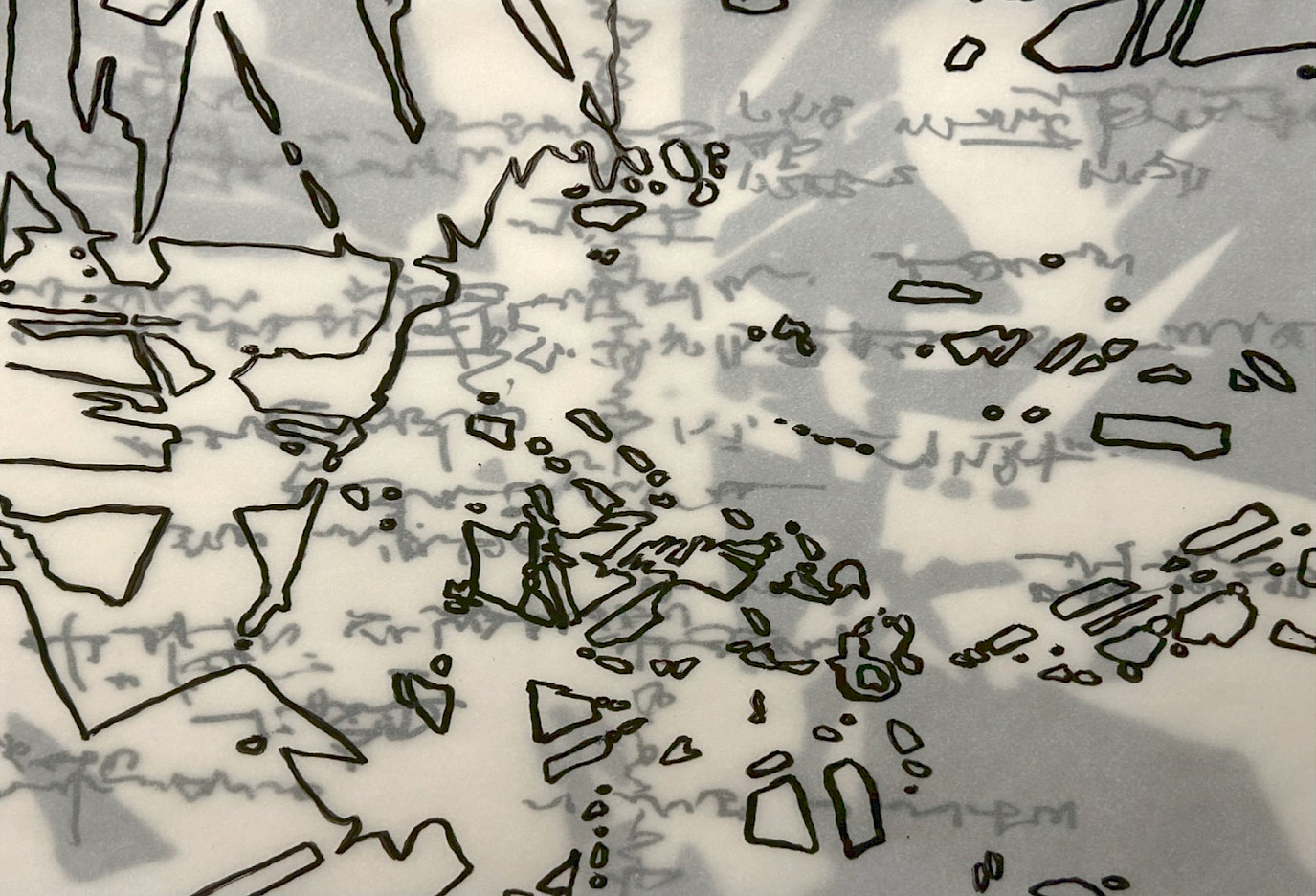

Magdalena Jetelovà became known worldwide as a sculptor of monumental wooden sculptures and as an installation artist. Her photographic work has also been attracting international attention for years. – In the large-format black-and-white photographs from the work cycles Atlantic Wall and Iceland Project presented in the exhibition, Jetelová deals with the topic of the border in a geographical, geological, philosophical and cultural context. – The Iceland Project is dedicated to the transatlantic ridge. This approximately 15,000 km long mountain range on the floor of the sea is part of a geological threshold system that extends over 70,000 km and spans the entire earth. Iceland is the only place where a continuous, approximately 350 km long section of the oceanic mountain range is visible above the water surface. In a way, this passage is the seam that once connected the continents of America, Europe and Africa. Here the continental plates still touch and move. At this geological threshold, Jetelová uses the laser to draw a light trail directly onto the terrain. In the process, seemingly abstract lines are created that meander, jump over geological stair formations, shorten expansive terrain ascents to vertical ones, disappear into depressions, begin again, cut through the spray of geysers and crashing waves, and finally lose themselves in the horizon.

If the Iceland Project is dedicated to a geological phenomenon, Atlantic Wall takes as its subject the line of defense built by the German Wehrmacht between 1942 and 1944 on the coasts of the Atlantic and the North Sea - the Atlantic Wall. Many of the bunkers, shooting and observation towers in the chain of defense against the expected Allied invasion were not destroyed after the end of the war, but were left to the natural progress of decay and forgotten. – Nature, with traces of the geological and historical change inscribed in it, becomes a foil for Magdalena Jetelová, a living, three-dimensional sheet on which the artist places light drawings as if the laser beam were her pencil.

The meditative as well as subtle and poetic works by the Irish artist and filmmaker Clare Langan tell of a world in flux, they reveal the beauty and tragedy of processes of change that occur in landscapes, in metropolises or in human relationships. – In Langan's almost mesmerizing film installation The Floating World (2015), the artist shows the Irish island of Skellig Michael on the very edge of Europe, which is home to one of the most inaccessible medieval monasteries in Ireland from the 7th century. The initial focus on Skellig Michael is followed by images of impressive views of the hypermodern metropolis Dubai and the Caribbean island of Montserrat. – In Langan's film the monumentality and grandeur of the landscape, which reduces any human presence to a minimum, contradicts the convention of its romanticising transfiguration. The temptation to identify with an apparently poetically charged landscape and to immerse yourself in nature proves to be a pathetic fallacy.

In her latest film The Heart of a Tree (2020), which Langan shot together with Oscar-nominated cinematographer Robbie Ryan in Iceland, the artist evokes the uncanny beauty of the world and combines images of dystopian landscapes with fantastic, dream-like sequences. There are places where time no longer exists, where above and below reverse and the air above the clouds becomes a new, unsafe ground. Perception, mind, memory, our knowledge of the world is put to the test. In these post-apocalyptic film landscapes everything is in motion - the elements water, earth, air, fog and clouds seem to float, light and sound (music: Jóhann Jóhannsson, Iceland) remove the viewer from the familiar reality. The central theme of the artist is again and again our civilization and its uncertain future, maybe even its end. - And yet Langan's imagery suggests what Martin Heidegger and once the Greeks called Aletheia: a place where truth reveals itself, a landscape that tells a story that is able to evoke a new world.

Curator: Jan T. Wilms

Kunsthaus Kaufbeuren

Spitaltor 2

87600 Kaufbeuren