“Now, during the time of this show, you are going to sing with us.

You are going to swing with the band, you’re gonna sing!

We call it a game. It is a spiritual game.

But, because our own kind of spiritualism is not accepted by the hierarchy,

we call it the underground spiritual game.”

FELA KUTI

Live at the Jazz festival Berlin, 1978

One Agreement presents new productions by Larry Bonćhaka (*1994, GH) and Samuel Baah Kortey (*1994, GH), MFA students at KNUST in Kumasi. The artists are developing a site-specific environment gravitating around colonial history, power structures and emancipatory potentials embedded in syncretic Christianity within the context of West Africa. The exhibition is paired with a public programme: a virtual panel discussion live-screened at fffriedrich with the artist and curator Khanyisile Mbongwa (SA), chief curator of the first Stellenbosch Triennale, the artist and curator Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh (GH), co-curator of the 12th edition of Bamako Encounters: Biennale of African Photography, and the artists.

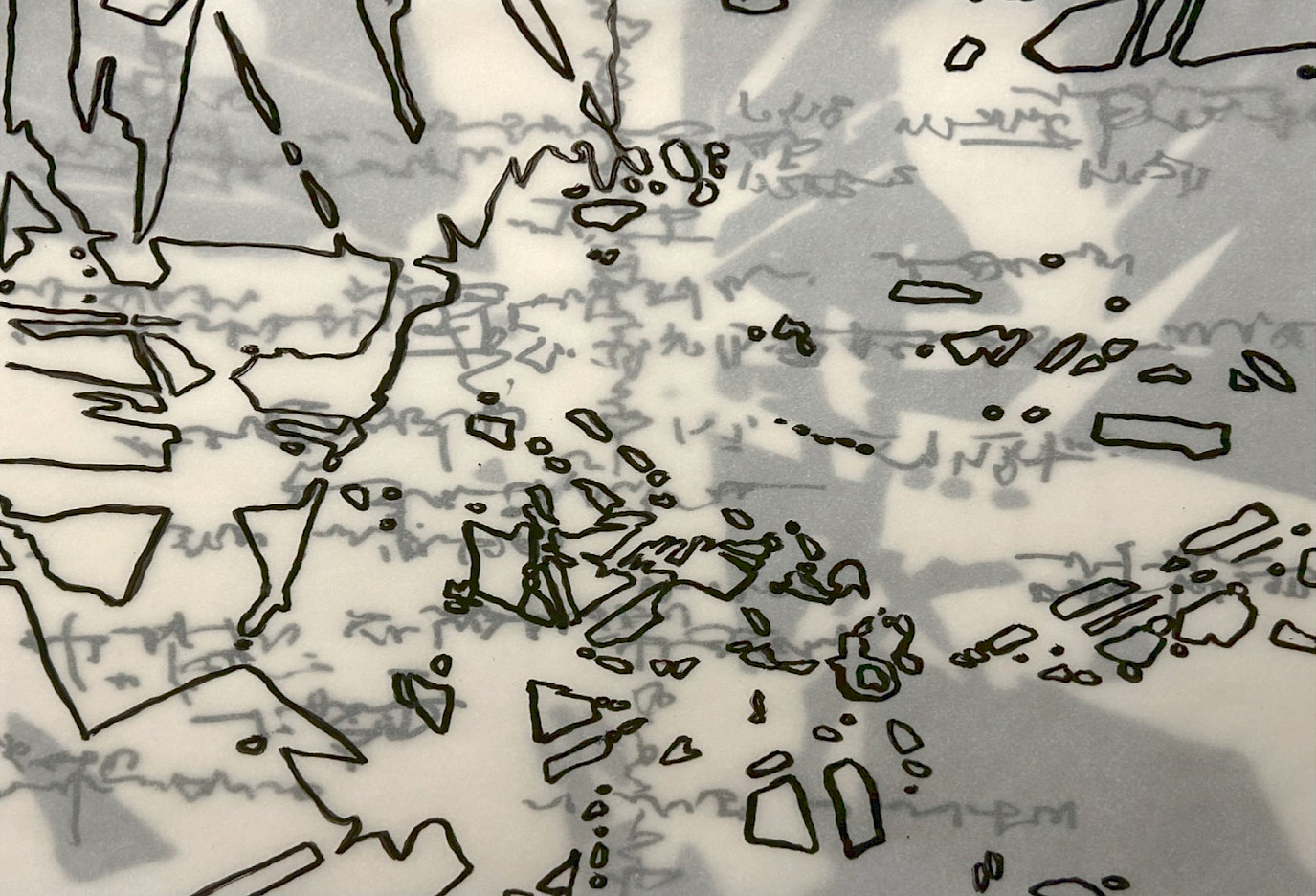

Currently based in Kumasi, Samuel Baah Kortey produced an installation consisting of a series of small-sized paintings. The spatial arrangement of the canvases borrows its shape from mullioned Gothic stained-glass window designs. While stained glass windows are meant to convey the spiritual quality of light and to prevent the believer’s mind from divagating into earthly matters, Kortey’s pictorial surfaces are made from animal fat and blood, grease and human hair. The artist deployed materials and techniques from butcher’s shops and restaurants. What the paintings display is not a transcending vector, but the immanent extent rooted in religious practices.

Larry Bonćhaka’s installation uses different household materials (as coffee, newspapers, water, cocoa, tree twigs, bird cage) to generate a trickling putrescent fish, quasi-piranha-shaped, agglutinated directly on the wall. A reference to the Ichthys, the ‘Jesus fish’, one of the oldest Christian symbols adopted as a secret visual code and initiates’ password during Roman persecution. This encrypted symbol played a major role in community-building under oppressive conditions. Often recurring in the Gospels (Mark 1:16-18, Luke 24:41-43, Matthew 13:47-5, John 21:11), the Ichthys catalyses a wide range of meanings from the holy Eucharist to Jesus’ acronym, from evangelisation to resurrection. Bonćhaka brings to matter the infinite, cyclic potential (∞ is also a fish) of community to struggle against political, social and cultural subjugation.

Kortey and Bonćhaka’s artworks orbit material dimensions of religious systems and practices. They target the ‘convergence of symbolic and material consequences enveloped in the immanent tensions of history and power’, to quote Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh’s recent essay In Praise of ‘Ghana Freedom’. Christianity is here not singled out as a movement of body deprecation, as a dogmatic philosophy of abomination of physicality or as a universalising weapon in the hands of colonial structures. It is observed, instead, with the lens of the many experiences the believers make of their own bodies, organs and existential conditions during a spiritual encounter with God, the Christian God, and the host of deities and spirits of traditional cults. In doing so, the artists summon the immanent potential of this multiplicity of bodies, human and non-human, in order to connect and to create a combative community against oppressive power.

Curated by Lorenzo Graf

fffriedrich, Alte Mainzer Gasse 4, Frankfurt am Main

Exhibition duration: 9th – 19th July

Opening times: Thursday – Sunday, 18:00-20:00, and on appointment

Opening: 9th July, 18:00

Panel discussion at fffriedrich: 9th July, 19:00

Panel discussion additionally live-streamed on: https://youtu.be/XeCKnX84Q-k

J’ACCUSE!

“My political strategy was […] to transform art from the status of commodity to gift.”

KĄRÎ’KẠCHÄ SEID’OU

Under which conditions has this exhibition been produced? Its makers encountered a quite telling barrier. fffriedrich is a project space which belongs to the Städelschule but shows made by the Curatorial Studies students are funded by the Goethe-Universität. When about to propose a concept for an exhibition in fffriedrich, students are told they can count on eight hundred euros budget. What is not communicated is the fact that they are supposed to advance the money out of their own pocket. For an average student, eight hundred euros is a considerable sum that can possibly cover a two-month rent for a room. Only who comes from a wealthy household (or who is willing to invest their hard-earned money as a full-time student) can afford this financial somersault. This very structure privileges those who are already privileged. I couldn’t afford to anticipate the money, and so my trouble was serious when, three weeks before the opening, I found out (after a month of institutional arm wrestling) that there was no alternative. Had it not been for the generous support of my classmates, who helped us drawing fully from the class budget, this exhibition could have never taken place.

According to Achille Mbembe (“Deglobalization”, 18 Feb. 2019), our neoliberal global condition is marked out by two parallel worlds. The first is the world of capital, the ‘Age of Animism’, which reduces the humankind into scattered individuals chained to their own desires. The second world is ‘the old world of bodies and distances, materials and areas, fractured spaces and borders — the world of separation.’

The same structure is strikingly at play as in the aforementioned case of the eight hundred euros advancement: a structure that privileges who is already privileged. Communal action is much more effective than a compliant acceptance of the ransom with which the current structure faces us individually. The eight hundred euros advancement is not an opportunity to grow. It promotes social and economic division among students. It replicates a system of inequality. Denouncing it, voicing it out loud, this is the only agreement we can reach.

“No agreement today, no agreement tomorrow.”

FELA KUTI, No Agreement

Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh is an artist, curator and writer based in Kumasi, Ghana. He is a member of the Exit Frame collective and permanently works in a curatorial capacity with blaxTARLINES KUMASI. He is co-curator of the 12th edition of Bamako Encounters: Biennale of African Photography and is presently a doctoral student at KNUST.

Samuel Baah Kortey is an artist based in Kumasi, Ghana. He is a member of two collectives: the Asafo Black Collective and blaxTARLINES KUMASI. He holds a BFA from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He finds interest in nature and loves experimenting with organic materials. He is currently pursuing his MFA at the Department of Painting and Sculpture, KNUST.

Larry Kojo Adorkor aka Bonćhaka is a Ghanaian artist whose practice revolves around a critical interest in identity politics, trade, material culture, mass production and architecture. He is a member of the Asafo Black Collective, who recently participated in the Stellenbosch Triennale. He is currently on an exchange programme at the fine art school Städelschule Frankfurt am Main from KNUST in Kumasi for his MFA.

Khanyisile Mbongwa is an artist, curator and sociologist based in Cape Town, South Africa. Her artistic and curatorial practices gained attention in the mid-2000s when she was part of the famous artist collective known as Gugulective. She was the adjunct curator for performative practices at Norval Foundation, and was appointed chief curator and artistic director of the first Stellenbosch Triennale.

Lorenzo Graf is a graduate student of Curatorial Studies at Goethe-Universtität and Städelschule, and holds a BA in Art History and Comparative Literature from Freie Universität. He initiated the exhibition series ‘Kunst im Wohnzimmer’ in collaboration with the open collective CONFINi.

Graphics:

Denyse Gawu-Mensah

Thanks to Zishi Han, Robin Riskin and Berlin. Special thanks to the MA Curatorial Studies class 2019/20, Asafo Black, Nane Ama Bentsi-Enchill, Janet Sosu, Arhun Aksakal and Fine Art Class. Personal thanks to Gabriele Rendina Cattani.

In memory of Şilan.