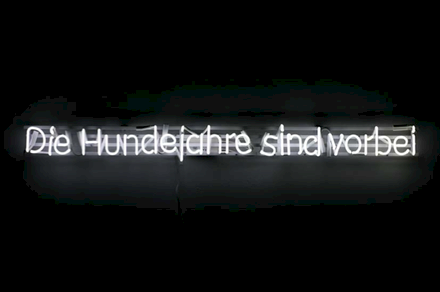

Titel

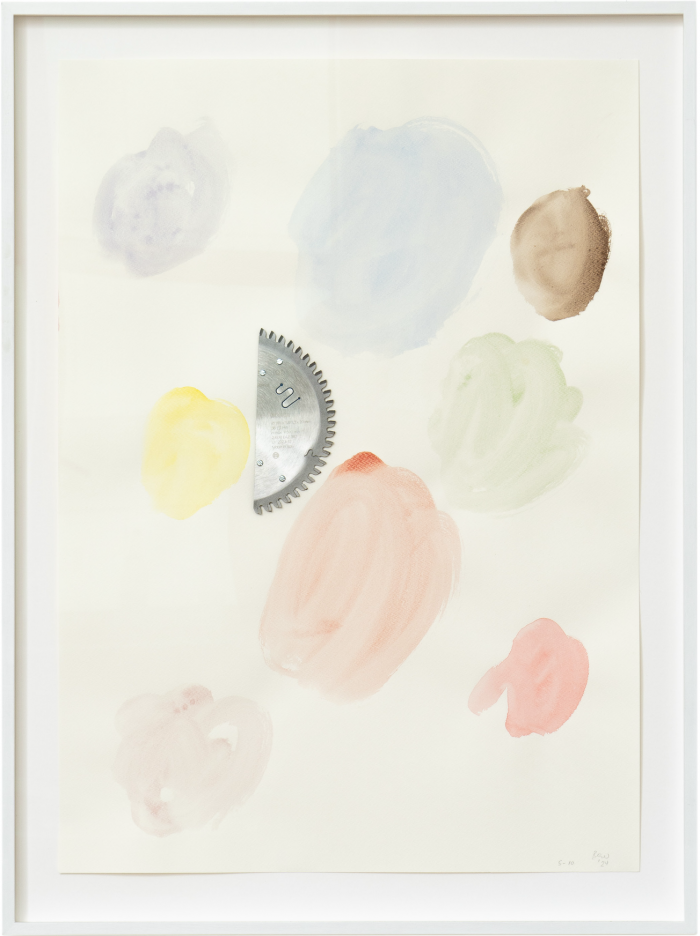

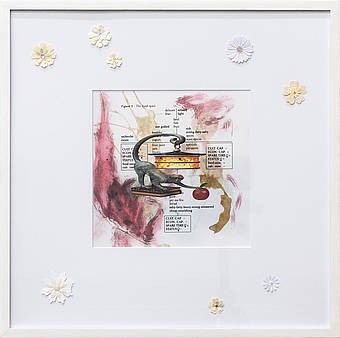

Venus Mirror (06.06.2012), 2012

Format

Spiegeldurchmesser 300 mm, Holzstütze (Optional): 35 x 50 x 10 cm

Auflage

12 + 4 Künstlerexemplare, jeweils nummeriert und signiert

Material

Teleskopspiegel (Parabolspiegel) F5.3 mit 6 Bohrungen, dazu optional: Holzstütze

Preis

€ 3900, Aufpreis für Holzstütze ca. € 150

Simon Starling (*1967 in Epsom /UK) erzählt mit seinen Arbeiten Geschichten; immer wieder zeigt er weitgespannte Zusammenhänge zwischen Orten, Dingen, kulturellen und historischen Gegebenheiten auf. Er selbst nimmt dabei die Rolle des Erzählers ein, der die Pointe nie direkt preisgibt, sondern meist den langen Weg sucht oder den Umweg geht, um anschließend in einer manchmal absurden Reduktion ein Netz von Bezügen darzustellen. Simon Starling ist Träger bedeutender internationaler Preise und Auszeichnungen, darunter des Turnerpreises 2005.

Als Teil einer weiterführenden Recherche zur Beziehung zwischen der Geschichte der historisch bedeutenden, aber heute überholten Beobachtungen des Venusdurchgangs und der Geburt (und bald Verschwindens) des Kinofilms auf Celluloid, verfolgt Venus Mirror (06.06.2012) die Flugbahn des Venusdurchgangs im Juni 2012 in Form eine Serie von Bohrungen in der Parabolwölbung eines ansonsten makellosen Teleskopspiegels. Hierzu Notes auf der Rückseite des Blatts.

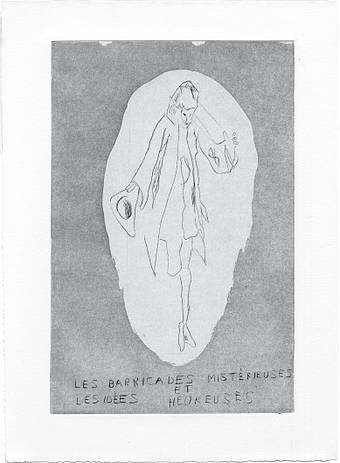

For many, Etienne Jules Marey’s invention of the chronophotographic gun, an instrument with which he managed in 1882 to capture the flight of a bird on a single glass-plate negative, marks a key generative moment in the evolution of cinema. However it is itself a direct descendent of an earlier device developed in 1874 by the French astronomer Pierre Cesar Jules Janssen – the revolver photographique. This telescope-cum-camera allowed for repeated timed exposures to be made around a single circular daguerreotype plate. Armed with this innovative piece of equipment, built for him in part by an accomplished Parisian clockmaker, Janssen set out for Japan in 1874.

One of a number of teams sent across the globe in order to record the rarely-visible transit of Venus across the Sun, Janssen and his colleagues hoped to refine the calculation of the mean Sun-Earth distance, the so called astronomical unit – the key to unlocking the architecture of the heavens. In large part lost or destroyed these extraordinary mirror finished donuts of silvered metal where deployed in the hope of refining the, until then, largely subjective business of timing the duration of the transit from geographically remote locations - a key part of the calculation process. Central to this refinement was the desire to conquer what was then a largely unexplained phenomena - black drop.

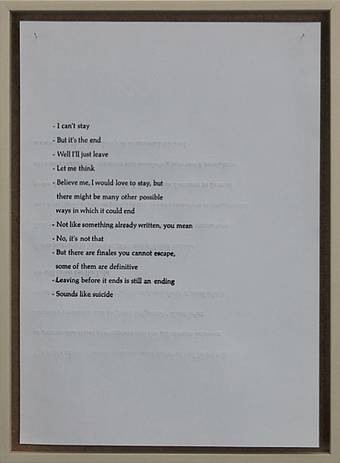

This mysterious visual effect, most famously observed by Captain Cook on the newly discovered island of Tahiti during the 1769 transit, resulted in the observer experiencing a distortion of Venus’ silhouette just as its edge was breaking away from the edge of the sun – making precise timing impossible. Agnes Clerke, in A Popular History of Astronomy (1902) vividly described the phenomena ‘as substituting adhesion for contact; the limbs of the sun and planet, instead of meeting and parting with the desirable clean definiteness, clinging together as if made of some glutinous material, and prolonging their connection by means of a dark band or dark threads stretched between them.’

It soon became clear that the results of the 1874 observations where no more objective than those of the previous ‘non-photographic’ observations, the various revolvers having produced very different and therefore incomparable results. A blow to the discipline of astronomy in general, the unravelling of the work surrounding the 1874 Transit led to a new approach to the problem of the astronomical unit – an approach dominated by another discipline, physics.

While the 1874 Transit, itself a quintessential, if reductive, cinematic experience - a shifty planetary protagonist projected by a vast bulb-sun onto the imaginations of an earth bound audience - may not have impacted greatly on our understanding of the solar-system, it could certainly be argued that Janssen’s innovative approach to chronophotography had a huge impact on the future of cinema. It is perhaps little surprise then that one of the first films ever screened in public was the Lumière Brothers footage of Janssen himself arriving for the conference of the Société Française de Photographie of 1895. Filmed in Lyon by Louis Lumière on the morning of the 15 June as the conference delegates arrived by riverboat, the film, that was screened for the first time that very afternoon, shows a stream of well dressed people walking down the gang-plank onto the quay. The delegates appear largely oblivious to the significance of the small wooden camera that survey’s their arrival, until that is Janssen himself appears, carrying his own camera. Noticing Lumière’s device and apparently understanding better than anyone its potential, and as if perhaps acknowledging his own importance in its genesis, Janssen pauses for a moment and theatrically greets the movie camera with a magnanimous flourish of his straw hat.

Wenn Sie Interesse an einer der Editionen oder Fragen haben, dann melden Sie sich gerne bei Martina Cooper.

Städelschule Portikus e.V.

Martina Cooper

Telefon: +49 (0) 69 60 50 08-13

freunde@staedelschule.de